By Ningombam Bupenda Meitei

Manipur is a state where the present Chief Secretary’s mother is considered to be a humble woman who raised her children by fishing and selling fishes. It is a world in itself where any old aged woman – who is, or almost, of the age of one’s grandmother – is honourably addressed as “abok” (“abok”, in Manipuri, means “grandmother”). “Abok” is even used to begin any conversation even with a grandmotherly woman who humbly sells her home-grown vegetables, not in a market but mostly sitting besides the footpath,that joins a road. The space of honour for abok in Manipuri society is measureless, but today the same Manipuri society needs to introspectively inquire whether the same honour is still being bestowed on abok in today’s world of Manipuris. “Abok”, which may semantically mean “grandmother” in English, has larger connotation with a sense of the guardian of “cultures, values, ethics, morality, principles and civilization” of Manipuri world. To meet and talk with abok, in Manipuri world, is almost akin to meeting and talking with Socrates, in Greek world. Abok is, indeed, the living treasure of Manipuri civilization.

What has happened to Manipur? Is it Manipur or Bandhpur (the land of Bandhs)? Is Manipur a laboratory of national highway blockades? Is Manipur a chemistry laboratory of testing the spirit and energy of different sections in competitively calling bandh or blocking of roads connecting districts or towns? There is even a joke of calling a bandh to demand that all the bachelors of Manipur, till they get their suitable brides, shall sit on a dharna and call for the bandh to meet their demands positively. To add more to this joke, the state’s Chief Minister – the elected Leader of the people of Manipur, under the Indian Constitution – stated, publicly, “Bandhs happen every time (in Manipur) and it is not new.”

The people of Manipur are also so used to Bandhs and Blockades that they also find hardly of any use even in discussing about Bandhs or Blockades, and this “hardly of any use” attitude is humbly and, perhaps – helplessly also, presented publicly by none other than the Chief Minister himself.

The fundamental question is asking the people of Manipur who are “not” used to Bandhs and Blockades, not because they cannot become used to them, but because they cannot afford to become used to them as that would put an end to their physical, biological and socio-economic existence on this planet. Who are these people of Manipur who are “not” used to Bandhs and Blockades?

Those who are not used to Bandhs and Blockades in Manipur may be a few, or none, or many, or all in the entire state of Manipur. But, there are two persons in which one is sure that that one could afford to become used to Bandhs and Blockades, while the other person cannot afford to do so at all. The one who could afford is the Chief Minister, notwithstanding who the Chief Minister is, at present. Then, who is the other one who cannot afford to do so like the Chief Minister?

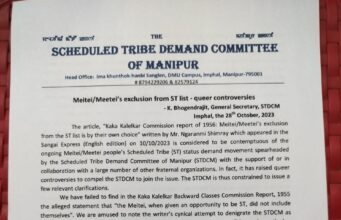

This writing of mine is dedicated to that person who is sure of both the inability and impossibility to afford to become used to Bandhs and Blockades in Manipur, and that person is none other than “the abok” who is seen in the photo presented, here. I don’t know her, I don’t know her name, I know nothing of her. I know one truth, and that truth is: she is “the abok” of Manipur. To me, she is not merely abok, she is the Socrates; through her, I could sense and feel the civilization of Manipur. But, when I see my Socrates – the abok – decaying but not ready to decay, dying but not accepting to die, I would like to know why she cannot look up, if she is at all alive on her own motherland.

The abok makes her every attempt to sell a handful of vegetables grown, probably with her grandchildren and daughter-in-law, at her house and carries them on her shoulder to be sold in a capital city called Imphal – which could almost become the birthplace of the 21st century’s Bandhs in the world. Her hands’ thinner, paler and aging skin becoming a support of her grey-haired head’s wrinkled temple, she chooses not to sit either on a government’s footpath or on a road constructed by the state, but on a land which is usually a place to throw garbage from the nearby shops. Taking out her old feet – that have travelled through the dusts of Manipur’s roads – from a pair of sandals, she has deeply thought and decisively determined to sit there and there itself. She, likes Socrates defying the Greek law, openly challenges the existing Manipuri society, which is being slowly poisoned by the madness of competing in calling Bandhs and Blockades, by not looking up to see herself. Deliberately, she chooses not to look up; she chooses to worry about her dying family but swallows the death by her courage to live not only for her but also for her family; she chooses not to look up, not because she cannot look up to see, but she does not desire to see the decaying Manipuri society, at present. She cries not because nobody has bought her vegetables, but only because she has every right to mourn the beginning of the demise of Manipuri society. She mourns because she can mourn; she can mourn because she knows; she knows because she is the abok, she is the Socrates of Manipur. If she does not mourn when today’s Manipuri society is poisoned by Bandhs and Blockades, then who – on the earth – would ever mourn for the world of Manipuri from getting extinct by almost continuously engaging Bandhs and Blockades, as if “those bandhs and blockades” are almost made to become synonymous with “oxygen of Manipur”?

The abok is also not looking up, not because she cannot look up; but because she does not want to look up to pragmatically realise the real existence of the Elected Leader of Manipur who says, “Bandhs happen every time and it is not new.” It could be, indeed, true that the poisoning of Manipuri society is taking place in a rapid swiftness every time, through bandhs and blockades, and such poisoning of the society is nothing new, and therefore, since they happen every time, the continuation of such poisoning will only further in the world of Manipuris. What would happen after some point of time from the effect of such continual poisoning? Will not it bring an end to Manipuri civilization? Will not it justify the dawn of the demise of Manipuri world? Will not it uproot the Manipuri society from furthering its generations for the next 22nd century? Will there be any future for Manipuri? Could Manipur exist without the world of Manipuri?

To some, the abok comes to sell some vegetables for the livelihood of hers and her family. To that “some”, she, instead of encountering the world of trade, needs to be cared and looked after at this age of hers. But, I do not have “that sympathy” of her being economically poor, financially not so sound, and hence, she has to come out to the world. Why do not I have “that sympathy”?

I also began writing this piece of mine, by being sympathetic about the abok but later got evolved into a maturity to understand why she comes out in the world. To those who think that she comes out in the world of markets, she is not. She comes out in the world, in the world of both ideas and actions where Manipuri society witnesses its own vibrant civilization and culture, in the world where the old people are not kept as “old people” but honoured as the liberated guardian of the society.

I started this piece by feeling that the abok’s physical, biological and socio-economic existence on this planet would come to an end as she cannot afford to become used to that poison in today’s Manipuri society, but I have failed myself in that feeling as an understanding has captured my mind. And, that understanding is the necessity for Manipuri society to wake up to put an end to getting used to that poison in the society. Since the abok cannot afford to witness the dusk of Manipuri civilization, therefore she cannot afford to become used to that poison.

I, too being – an ordinary soul, could not stop my tears flowing while seeing this deeply moving photo, but while writing this piece of mine, not those rolling tears have merely rolled down but flowing tears have cleansed my eyes. And, only with those deeply cleansed eyes, I could see why this abok needs no sympathy from Manipuri society but Manipuri society, instead, must cleanse its eyes to understand – why she does not look up, why she hides her face.

To those who have not let their tears naturally flow when they see this emotionally touching photo, and who have not cleansed their eyes with those tears to clearly see and understand the wisdom in the abok – the Socrates of Manipur – to introspect the existing Manipuri society, it is undoubtedly clear and rightfully admissible that you either have not visited Manipur or are not a Manipuri, or are not a humanist.

Oh, Manipur! Do not see the photo as you see. Can you really see yourself in the same photo as you see the photo in front of you, at present?

Children of this hardworking mom must be ashamed of her plight.

So heart touching

EMA ng na wari do ei su khangi EMA ei gisu EMA leiye…

Ima ge damak ta yamna nungaijady,ma c pumba l

Kuireda khngva

laibak feidako kanagi mamabu oiramgadouba. Adunani niraga chagadoubagi mahut pot yollaga hinglise, leibiyu maipakna mai thanggatlaga hingnaba.

Sigumba imasing sida akal aring singduna bdf,traffic police,police singna pot cheikhaiduna manghanbiri .

Ema ebemmabu Esorna thoujanbiba oisanu matam chuppda.

Pukning nungshida.

Seriously bro. . ..

It’s an emotional picture u uploaded , my bro. I think that it could be the best to upload another picture about you bought all those vegetables but I hope u didn’t buy a single bundle …Only uploading such a type of photo will not give message , yes , u can widely spread message by taking photos of buying all those vegetables from the poor mother but not bargaining .

Oh no, I cant

Yengheideda hoirongi matouni mahaki kana mata leitraba ahanse thigatlubda mathong chadaba amadi seidangba oirmba nakta oina toue assss leibakse sigumba yam thoklakhini

areiba asi faoba eramdam asigi mioina leibide.mayang gi potna mamal yaammi lou e khalli etamdamse yengbada nungsidro?

Chanbe Duna see gum ba vegetable yonba theng narade loina mak lei drasu ayouba paisa Duna loina leibeyu ko request ne

Love u mummy