BY GERALDINE FORBES

What to wear?

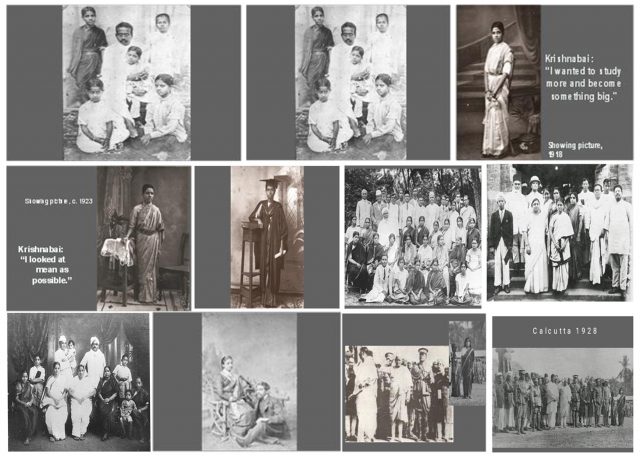

Second, I want to present some of the issues related to dress, hair and shoes that emerged from the interviews with women. The many references to items of clothing and frequent anxiety about what to wear marked this generation whose lives were decidedly different from those of their grandmothers. These “new women” were attending schools and colleges, joining women’s groups to help less fortunate women or to lobby for women’s rights, entering the ‘respectable’ professions of teaching and nursing, and appearing at political meetings. They were breaking with tradition by assuming public roles and entering spaces usually reserved for men but the records are generally silent about the material aspects of their new roles. And this is where photographs are immensely valuable because they are visual texts that can be read for sartorial details and, when people look at them, they remember and recount their anxieties in the past.

By the l870’s there were many ways of combining the blouse or jacket with petticoat and sari for events outside the home.

Slide 31

The woman most frequently credited with introducing a new way of dressing was Jnanadanandini Devi, the wife of Satyendranath Tagore who introduced a modification of the Parsi sari to Bengal. It was at Brighton that this remarkable photograph, with her husband- Satyendranath Tagore – seated at her knee, was taken.

Slide 32

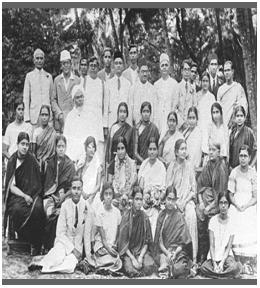

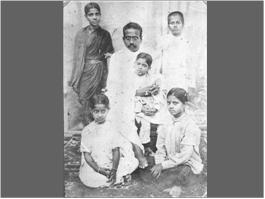

My second example can help us understand some of the challenges faced by a generation of women who participated in public forums for the first time. When Krishnabai (front third from the left) showed me this photo, she explained she had just given evidence to the Age of Consent Committee in 1927. However, instead of talking about her presentation, she remembered the “what to wear” challenge faced by young unmarried women in Madras. Girls wore a skirt and the half-sari while married women wore saris – in her community, a 9-yard sari. Krishnabai, born in 1906, was in her early 20s but still unmarried when this photo was taken. In a quandary about what to wear, she decided to create a style of her own.

My second example can help us understand some of the challenges faced by a generation of women who participated in public forums for the first time. When Krishnabai (front third from the left) showed me this photo, she explained she had just given evidence to the Age of Consent Committee in 1927. However, instead of talking about her presentation, she remembered the “what to wear” challenge faced by young unmarried women in Madras. Girls wore a skirt and the half-sari while married women wore saris – in her community, a 9-yard sari. Krishnabai, born in 1906, was in her early 20s but still unmarried when this photo was taken. In a quandary about what to wear, she decided to create a style of her own.

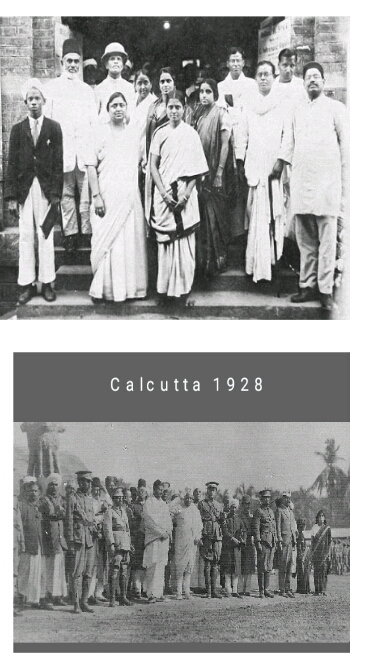

A similar challenge arose for young women who planned to march, with young men, at the annual conference of the Indian National Congress to be held in Calcutta in 1928. Colonel Latika Ghosh, the political activist organizing college students and women teachers for this event, was deeply concerned about their costume. She finally decided on a black sari with green and orange border worn over a white blouse. When people wanted the female volunteers to dress like the males—in trousers and boots –but Latika refused. The women marched, in this uniform, and according to young women at the event, inspired them to take part in the freedom struggle.

Slide 33

Unfortunately, the iconic photo of that event does not include any women and the “proof” of women’s participation survived only in a private collection of photographs.

Unfortunately, the iconic photo of that event does not include any women and the “proof” of women’s participation survived only in a private collection of photographs.

There are many other examples of women’s memories of this time that remind us that these changes presented material as well as social and psychological challenges.

Images and the remembered past

Slide 34

My third example problematizes the memory evoked by past images. This is not a new subject, historians have long been suspicious of memory and urge us to analyze memories. Interviewing Mexican American women who had been involved in an important strike in 1974, Emily Honig noticed they reached back in their life histories to recount events that would explain their transition from loyal workers to rebellious union leaders. Krishnabai Rau Nimbkar (b. 1906), who lived in Madras where her family was part of a tightly knit Maharashtrian community involved in government service. Krishnabai’s father and mother were both interested in social reform and they encouraged debate on current social and political issues. Krishnabai’s mother, Kamalabai, was married at age ten but educated before she was sent to live with her husband at 15 years of age. In Madras city, Kamalabai joined a number of progressive women’s organizations.

My third example problematizes the memory evoked by past images. This is not a new subject, historians have long been suspicious of memory and urge us to analyze memories. Interviewing Mexican American women who had been involved in an important strike in 1974, Emily Honig noticed they reached back in their life histories to recount events that would explain their transition from loyal workers to rebellious union leaders. Krishnabai Rau Nimbkar (b. 1906), who lived in Madras where her family was part of a tightly knit Maharashtrian community involved in government service. Krishnabai’s father and mother were both interested in social reform and they encouraged debate on current social and political issues. Krishnabai’s mother, Kamalabai, was married at age ten but educated before she was sent to live with her husband at 15 years of age. In Madras city, Kamalabai joined a number of progressive women’s organizations.

Slide 35

However, the eldest daughter, Indirabai, the eldest daughter, was married at age 12 because the family received a proposal from an ideal suitor. The second daughter was also married young (shown here with her husband – occasion, 1917 – birth of first grandchild).

However, the eldest daughter, Indirabai, the eldest daughter, was married at age 12 because the family received a proposal from an ideal suitor. The second daughter was also married young (shown here with her husband – occasion, 1917 – birth of first grandchild).

Slide 36

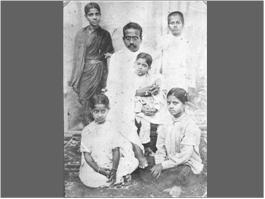

Her father’s ill health would have put the topic to rest were it not for relatives. When Krishnabai was visiting Bombay, they took her to a studio and ordered a showing photograph. Then in the ninth standard at school. Krishnabai wanted to continue with her studies, not get married. In an interview for the Nehru Library, Krishnabai recalled “[My mother] wanted me to grow up and get an education. I had also come to form firm views and opinions on whether I wanted to marry early. I wanted to study more and become something big.” However, she had no choice but to comply with her relatives’ wishes and assume a fashionable pose.

Her father’s ill health would have put the topic to rest were it not for relatives. When Krishnabai was visiting Bombay, they took her to a studio and ordered a showing photograph. Then in the ninth standard at school. Krishnabai wanted to continue with her studies, not get married. In an interview for the Nehru Library, Krishnabai recalled “[My mother] wanted me to grow up and get an education. I had also come to form firm views and opinions on whether I wanted to marry early. I wanted to study more and become something big.” However, she had no choice but to comply with her relatives’ wishes and assume a fashionable pose.

Slide 37

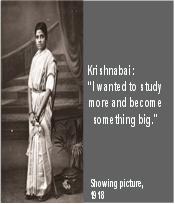

When Krishnabai’s father died in 1922, Kamalabai was already taking care of her ailing and widowed mother. With the additional burden of two children to educate, Kamalabai sold their house and found a job as matron in a Home for Women. Krishnabai won a scholarship to attend Queen Mary’s College and would have happily continued with her studies, but family members wanted her married. They insisted she pose for this second showing photograph. Krishnabai resisted this time, and said about the experience: “I looked as mean as possible so that no one would want to marry me.”

When Krishnabai’s father died in 1922, Kamalabai was already taking care of her ailing and widowed mother. With the additional burden of two children to educate, Kamalabai sold their house and found a job as matron in a Home for Women. Krishnabai won a scholarship to attend Queen Mary’s College and would have happily continued with her studies, but family members wanted her married. They insisted she pose for this second showing photograph. Krishnabai resisted this time, and said about the experience: “I looked as mean as possible so that no one would want to marry me.”

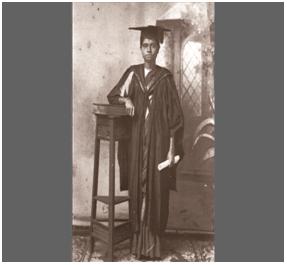

Slide 38

It may have worked for there is no evidence of proposals and Krishnabai was able to attend Madras University and complete a BA in Zoology, join the Gandhian movement,

It may have worked for there is no evidence of proposals and Krishnabai was able to attend Madras University and complete a BA in Zoology, join the Gandhian movement,

While “the look” may not be obvious to the casual viewer,1 Krishnabai believed it would deter prospective mothers-in-law.

[*] Padma Anagol thinks the look is obvious, she wrote: “I compared the two photos and . . . thought in the earlier one she looks unhappy but downright grumpy and unhappy in the second one – note the lips are put not in a ‘pout’ but literally brought down like a snarl. She looks really ungracious in the second.” Email communication August 18, 2005.

Slide 39

Slide 40

and marry the man of her choice, Dr. V. D. Nimbkar, in 1932 She then became a medical doctor and continued to be a political and social activist until her death.

and marry the man of her choice, Dr. V. D. Nimbkar, in 1932 She then became a medical doctor and continued to be a political and social activist until her death.